APIs: “Anyone can build an app with these things!”

Last week I was chatting with a friend about the sheer scope of apps available on every app store these days. When smartphones were still in their infancy, I remember someone making a mint on an app that made lightsaber noises when you waved it around – everyone with a smartphone knew about this app. That sort of thing is completely undiscoverable in an app store now, buried beneath a collection of AAA apps made by enterprise level companies and indie apps made by folks in their basements. I commented on the number of apps and was met with the response: “Anyone can make an app these days with the new stuff, easy IDEs and APIs.” While I agree that development has gotten easier or at least the bar for entry is lower, I don’t think APIs have a lot to do with that.”

“Just jam it in there.”

When I was 18 my friend Ray got a new video card for his computer so we could play a new game together. Neither of us had any experience installing a new card in a computer, but I was back from college and studying computer science, so he asked me to try. The card had cost a few months of savings for us, and I can’t describe the anxiety I felt as I tried to jam it into the motherboard slot that seemed way too small to fit the huge fan spinning video monstrosity. I was reassured, however, by the logo appearing on the packaging and circuit board of the card itself – Plug and Play.

In the 80’s and 90’s, PCs were transitioning between hobby devices used solely by makers and computer enthusiasts into household devices the average person needed to be able to operate and upgrade. Swapping new cards and devices in and out of your PC was notoriously difficult at the time, both in risk and actual physical strength required. Once you had the card seated correctly, then the REAL fun began as you attempted to locate and install the correct drivers for the device, and hoped the floppy disks that had come in the box were not corrupted. The Plug and Play design that arose was genius in its design – simply seat your card, turn your computer on, and your computer would find the device, install and configure the software for it automatically and you’d have your new video or audio card or network card. We still use it today, as it’s basically one of the main features that makes interchangeable and modular mobile devices possible. In its early implementation, however, we didn’t call it Plug and Play. We called it Plug and Pray.

While the idea of early PnP was to simplify the software configuration process, the variance in hardware specifications and the speed at which new hardware and software developed made pre-internet PnP a Russian roulette of spaghetti’d drivers and applications. Machines would automatically update to bad drivers, multiple PnP devices would overwrite each other’s configurations, and every so often something would go so wrong as to damage your hardware. Which is exactly what happened to my friend Ray and I, as I managed to fry both his card and his motherboard by futzing about with the PnP overclocking settings on a mis-seated card. Still sorry, Ray.

API functionality is like Plug and Play – in theory

The design philosophy behind Plug and Play is virtually identical to the philosophy behind the API; abstract the nitty gritty of solving a problem away from the user and lower the complexity bar for accessing the solution. In other words, take an expert technical tool and make it a consumer product. With an API, generally the “tool” you’re turning into a “consumer product” is data, and the consumers are applications that gobble it up.

The advantage to this approach is that it makes data sharing between applications so easy that it makes sense for each feature of an enterprise level application to be a “best in breed” suite of mini-applications providing consumable API data interactively. This modularity leads to the illusion that it’s easy to just plug in applications that are API-supported into larger development efforts. Even with an API providing clear and efficient access to the product of some applications’ functionality, integrating that functionality into a larger application is still not simple. The main disadvantage of the API-based development approach is complexity.

Apps are no longer standalone tools

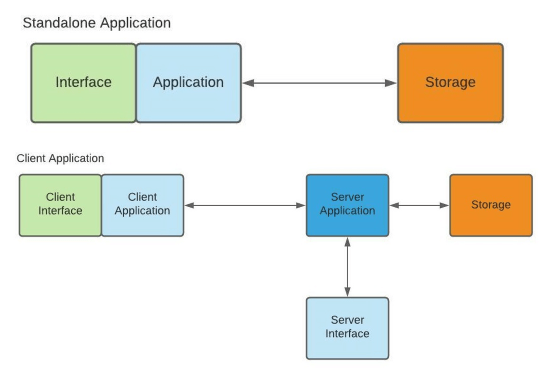

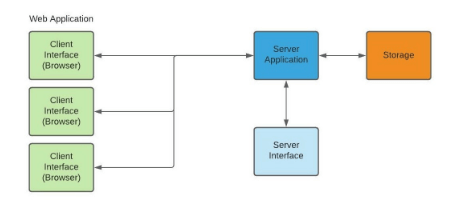

The idea of what an “application” is has changed significantly over the years, but we often still think about its development in terms of the standalone apps of earlier eras. There will be some interface that displays functionality, an internal application that makes the feature sets operate, and storage.

Even the advent of earlier web applications, when processing was being offloaded from personal machines back onto server farms was simply a return to the dumb terminal/mainframe applications.

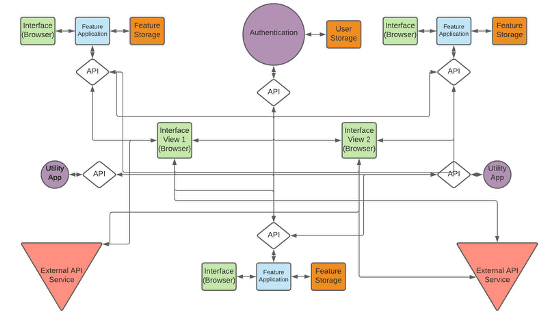

Applications could easily be split into workflows, environments, stacks, and software lifecycles, because an application was a “distinct” entity. With the widespread adoption of the API based “best in breed” development model, even thinking about a project as an “application” is becoming an outmoded concept, because what we are really building are systems and infrastructures. An extremely simple API based application might look something like this.

There is no simple left to right or down to up workflow in a modern application, which means there is no “slot” in which to “slot something in”. Every addition to the application requires architectural design, infrastructure design, and workflow design before you even begin approaching things like User Interface design.

In addition, the distribution of applications to many different locations means that modern applications have to build systems to replace concepts they would get “for free” in standalone applications – things such as time synchronization. Just keeping the various pieces of your application on the same time system can be a massive undertaking; one of the most common bugs in large software systems over the last 20 years has been unsynchronized timestamps between servers.

The API environment is becoming more complex

Because APIs are now used as internal application data sources, they’ve become useful for passing more than just raw data. APIs will now pass around code blocks, dynamically alter themselves on the fly based on responses from other APIs, or simply get created, configured, and torn down all by software in the background.

While APIs simplify a great deal of the technical nuts and bolts of different applications speaking to one another, that simplification has boosted the overall craft of development into a new era of design that may be far more complex than anything previously “on the shelf”. The assembly line made cars more complicated to build, not less, because each piece could now be assembled in a fraction of the time, freeing up that time to be able to build more complicated and useful pieces. One individual part of assembling the car is now easier, but the action of assembling an entire one and having it work moves from a set of Ikea instructions to the realm of creative art.

Engineers, Not Coders

The growing complexity of API-based applications is the stretching of the long arm of technology, doing what it always does. It is the latest software realm that encourages the shift in job titles from “programmer” to “engineer”. Modern applications are feats of architectural engineering on par with skyscrapers.

APIs have become ubiquitous enough to pop up in marketing and executive chats about how to make and sell products. It’s a great thing when tech is transformative enough that it deserves to be in those conversations. But, they are not a silver bullet when it comes to allowing faster or lower cost development. They’ll allow your applications and networks to grow and change as needed, helping to future proof your IP and data workflows, but they often make building and maintaining things in the here and now more difficult and time consuming.

You need engineers to build and maintain your APIs, not just programmers, because they need to be keeping an eye on the structural integrity of your entire system, not just the little piece they’re touching. That requires expertise beyond learning Javascript or Ruby on Rails–expertise only gained through time and experience working on complex systems.

60 Minutes or 60 hours

We would rather spend 60 minutes of our time to save you hours of unnecessary time planning, implementing or fixing errors in building out your digital capabilities. We enjoy challenges, and expect that you prefer avoiding risk.